Laurel Canyon Radio’s Top 10 Albums of 2017

Laurel Canyon Radio’s Top 10 Albums of 2017

Seven years have passed since Oldham-born, Nashville-based Karen Elson released debut album The Ghost Who Walks, a work that was notable less for its solid collection of murder ballads and blues jams than the person who produced it: the model and singer-songwriter’s then-husband Jack White. In the time since, the pair have undergone a not terribly amicable separation (though are reportedly now friends), and Elson’s musical tastes seem to have drifted away from White’s bluesy leanings and towards something more luscious and Laurel Canyon-esque.

Double Roses is produced by long-time Father John Misty collaborator Jonathan Wilson, and features the sort of orchestral flourishes present in Misty’s own work. (Misty himself appears on the album, along with Laura Marling and – rather contentiously given his band’s acrimonious history with White – Pat Carney of the Black Keys.) As with her previous album, it’s tidy and tasteful rather than gripping, with the exception of the wonderfully beguiling title track, a swirl of arpeggiated harps and hushed melodies.

That’s certainly the feeling of the working class folks who populate Slaid Cleaves’ songs, and is likely shared by the singer-songwriter too. While he might not be laboring in a dead end job, Cleaves clearly understands the isolation of those that do, singing about their frustrations, futilities and disappointments in a smooth, easygoing voice that nevertheless captures the hopeless feelings of so many Americans.

Look no further than the album’s title or the bleak sepia-toned cover photo of bare trees alongside an empty highway to understand this is not going to be the disc you throw on to liven up your next party. Cleaves’ eighth studio release comes four years after his previous under-the-radar gem, 2013’s Still Fighting the War, but little has changed in his rather gloomy world view.

“I don’t need to read the papers or the TV to understand/ that this world’s been shaved by a drunken barber’s hand” he sings atop a modified reggae beat, and that dour outlook extends to most of these dozen songs. There’s a Springsteen/James McMurtry defiant, driving strum to rockers like the opening “Already Gone” (not the Eagles tune), where he sings “over and over we try and we fail/ to figure out this game we’re all in,” and a tough Old 97s vibrato twang to “Take Home Pay” (“we’re all scrapping for the Do Re Mi” he sings, referencing Woody Guthrie, a philosophical influence).

But most of the tunes stay on lower boil, the better to absorb Cleaves’ sharp, concise and often revelatory word play. He generally sings in the first person; of a reflective loner who has seen his share of pain, appreciating yet almost dismissing a sunnier personality in a woman on the melancholy “If I Had a Heart.” He then cherishes the warmth and intimacy of a long-time relationship on the “So Good to Me,” one of the disc’s few instances of pure positivity set to an appropriately jaunty melody.

More often Cleaves sings of broken souls yearning for something … romance in the bittersweet “To Be Held,” and to have his son appreciate the old car he restored with love over the years in “Primer Gray.” Mostly though, songs such as “Little Guys” deal with losing what he sees as the good old days of small town America to technology and the increasingly chilly dominance of big business.

It may not be tilling new ground, especially for him, but Cleaves brings such warmth, tenderness and humanity to his songs that you’ll be hanging on his words and getting lost in the worlds of characters most of us are familiar with.

In many cases they may even be us.

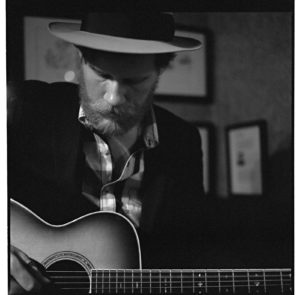

8) “Poor David’s Almanac” – David Rawlings

David Rawlings finds news ways of inhabiting old folk music alongside his longtime musical partner Gillian Welch. There’s a crisp intimacy to his new solo effort, but also a self-awareness.

Poor David’s Almanack is David Rawlings’ third album or his eighth, depending on how you count. In the last 10 years, he’s made two records as the Dave Rawlings Machine, a loose reference to the old Woody Guthrie slogan, but he’s made five more with his musical partner Gillian Welch under her name. They both play on each other’s record, they both inform the direction each other’s music takes, but they maintain separate musical identities. Yet, their combined catalog comprises perhaps the most ambitious and most peculiar corpus in roots music today, one that digs deep into the past to find neglected song forms and defiantly old-timey notions: new ways of old singing, of just inhabiting the music.

His latest is credited to just David Rawlings, but it features Welch and members of the Machine. He remains the most prominent personality on the album, and he’s a fine singer with a slightly nasal twang, a way of bleating his vowels that belies his New England origins. Listen to Rawlings dive into the chorus of “Lindsey Button,” drawing out each syllable: “A long time ago.” There’s a full decade in each word. He’s an even better guitar player, with a graceful picking style and a full bag of tricks. When he bends his notes on “Airplane,” he adds an earthbound dissonance to its airborne chorus. In his songwriting, Rawlings favors the repetition of the blues and the wily phrasing of folk. He rewrites the old tune “Cumberland Gap,” popularized by Guthrie and Lonnie Donegan, into a third-person tale of lost love and hard times.

Rawlings, Welch, and the backing players use the same instruments available to any roots musician, but very little roots music sounds quite like this. That’s partly due to Rawlings’ production. He’s lent his touch to albums by Ryan Adams, Bright Eyes, and Dawes, and has a notoriously discriminating ear, to the extent that he and Welch are only just now releasing vinyl editions of their albums after 15 years of unsatisfactory test pressings. There’s a crisp intimacy to the record, but also a self-awareness. He and especially Welch were long dogged by criticisms of “inauthenticity,” which might have more to do with her L.A. origins, but they’ve managed to outlast them. Still, there is useful playacting to their music, as though they understand that any 21st century folk singer necessarily has some distance on their subject.

7) “Way Out West” – Marty Stuart and His Fabulous Superlatives

Way Out West is Marty Stuart‘s album-length paean to the myth and magic of the American West. It finds country’s stalwart neo-traditionalist turning cosmic cowboy for a journey through the Joshua trees, shadowy canyons and desert dreams that tantalize travelers with the promise of a golden shore on the other side.

Stuart grew up in Mississippi, captivated at an early age by glimpses of the West like the Bakersfield sound of Buck Owens, and the cowboy ballads of his namesake, Marty Robbins. Having made his mark on country over the last four decades, first as a guitarist with Flatt & Scruggs and Johnny Cash and then as a reliably roots-conscious solo artist, Stuart takes the occasion of his 18th album to bring his Western preoccupation full circle with a moody, atmospheric song cycle.

Naturally, Nashville wasn’t the place to make this kind of record, so Stuart called on his old cohort Mike Campbell, guitar hero for Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, who produced the album at Hollywood’s iconic Capitol Studios and his own recording headquarters. The pair first met when Stuart joined with Petty’s gang to back Johnny Cash on The Man in Black’s 1996 Unchained album. And Campbell’s co-production of Petty’s 2010 release, Mojo, bore a bit of the heady desert-trip vibe he and Stuart have cooked up for Way Out West.

After conjuring up some ancient spirits with a swirling snatch of audio collage called “Desert Prayer” that blends the sound of Native American ritual with some rather psychedelic sitar splashes, Stuart offers up “Mojave,” the first of several instrumentals that punctuate the album, luxuriating in the kind of deep-diving guitar reverb that evokes the grand echo of the desert canyons.

Those plangent guitars return on “Lost on the Desert,” a Buddy Mize/Dallas Frazier tune Johnny Cash released in 1962 that shows the desert’s dark side; an escaped convict desperately searches for his buried loot, foiled either by fate or the devil himself, depending on which way those dry, dusty winds blow. Way Out West‘s title track works the Cash legacy and a multitude of other elements into its lyrics, crafting a trippy travelogue that moves from Arizona to California and finds the narrator addled by taking too many pills, eventually having visions of everything from scorpions and poisonous ants to aliens. It feels a bit like what might have happened if Woody Guthrie had written his California-dreaming “Do Re Mi” during the temptation of Christ in the Judaean Desert.

Just in case the proceedings didn’t already feel cinematic enough, the Mexican-tinged instrumental “El Fantasma Del Toro” comes off like a lost Ennio Morricone spaghetti western theme. On the freedom-across-the-border ballad “Old Mexico,” Stuart makes his contribution to country’s Mexican fascination, picking up where Marty Robbins left off on tunes like “El Paso.” Stuart sings of Mexico as a place for potential reinvention, where “there’s no price on my head, I can live and I can breathe and come back from the dead,” just like the fresh start California has historically represented for searchers from the early settlers’ era to the dust-bowl days and beyond.

More spirit visions arrive amid cosmic lyrics worthy of the late Byrds songsmith Gene Clark as Stuart stokes a ’60s rock vibe on “Time Don’t Wait.” Chiming guitars riffs, wah-wah pedal swells, and a nimble Beatles-indebted bass line bring a gently psychedelic feel, like the comedown from a desert peyote buzz.

That Fistful of Dollars feeling returns on “Quicksand,” another evocative instrumental, but this time it dovetails with the ’60s sun-and-fun side of Western culture by tapping into a surf-rock vibe. If Morricone could have collaborated with surf guitar god Dick Dale, the results might have been something like this. The track leads into a cover of the Jim & Jesse bluegrass standard “Airmail Special,” reinvented as a burning honky-tonker and returning to the California-as-promised land-theme with its plane ride “over plains and high, dark mountains” to the Golden State.

After another desert-surf twang-guitar showcase (“Torpedo”), a melancholy love song distinguished by a string quartet (“Please Don’t Say Goodbye”) and Stuart’s classic-sounding addition to the country catalog of white-line-fever trucker anthems (“Whole Lotta Highway (With a Million Miles to Go)”), things come to a close on a reflective note. The quiet, almost hymnal “Wait for the Morning” promises redemption through a flight into the rising sun.

The closing credits of Stuart’s movie for the mind (and ears) would scroll to the instrumental reprise of the title track. All the elements woven through the record come together for a final bow, as surf music, spaghetti western soundtracks, psychedelia, and cosmic country merge in celebration of the idealized West that Stuart’s album brings to life.

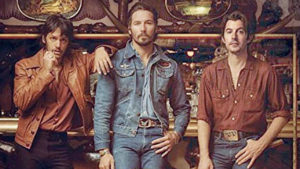

6) “On The Rocks” – Midland

Although Midland has struck mainstream country gold with their single “Drinking Problem” and the consistently tuneful songs that accompany it here, there is something so retro-y reminiscent of 1970s Eagles via George Strait (or vice versa) that’s it hard not to anticipate the exciting directions in which these three fellas could go in the future.

5) “Ready The Horses” – Jarrod Dickenson

Recorded live to tape in the UK, ‘Ready The Horses’ is an album by the Nashville based, Texan singer songwriter Jarrod Dickenson who isn’t so much a man of contradictions, as a musician following his muse.

‘Ready The Horses’ is a melange of country, soul, blues and Americana with a confessional singer-songwriter bent, that demands focused attention. Dickenson draws us into heartfelt narratives with enough substance to avoid cliché.

Jarrod Dickenson is self evidently a confident singer-songwriter with something to say. From the unabashed opening line of ‘Faint Of Heart’, he draws the listener in on the back of a tremolo laden shuffle which sounds like an old bluesy work song: “No this ain’t for the faint of heart, No You’ve got to be strong, ‘cos it’s bound to go wrong”.

As in the classic opening scene of a film, it’s the power of suggestion that carries us through a cross-genre roots album cemented by real songcraft.

A combination of strong songs with a contrasting vocal vulnerability draws us into an album title that conveys the feeling that we’re being taken on a journey.

He moves from the soulful, bluesy retro feel of ‘Take It From Me’, to the more brusque ‘Gold Rush’, a tale of greed and foreboding on which the clanking percussive backdrop evokes a dark Tom Waits style narrative.

You suspect he’s happiest on the gentle acoustic duet with his wife Claire, ‘Your Heart Belongs To Me’. It’s voiced over a distant pedal steel on a number with lovely contrast. And it’s that balance of contrast and flow, with occasional bv’s and nuanced dynamics that gives the album its punch.

Each track reveals more layers of the onion, as Dickenson explores his song craft through the mood and feel of the music, and lyrical depth that rarely wastes a word.

The single ‘California’ is the perfect example of his craft. The pedal steel-led, meditative piece is the perfect foil for his emotive whispered vocal over a sub-waltz accompaniment, which builds impressively and flows into the hook.

It’s another example of the way the music and lyrics lock together, with occasional layered instrumentation proving an extra dynamic to the songs.

On ‘Way Past Midnight’ the clickety-clack rhythm could be Paul Simon, as it evokes a colourful narrative full of expectation: “This night has just begun, music is playing, the ladies are swaying, gonna dance until the dawn.”

‘In The Meantime’ is full of space and time, and draws us back to his country roots with a soulful horn arrangement. It’ s a well paced, subtly arranged relationship song, on which the sudden emphasis of the piano, organ and bv’s gives it a notable lift, and provides the perfect backdrop for his eloquent phrasing.

The Texas backdrop of ‘A Cowboy & The Moon’ probably narrows his appeal, but there’s no denying the emotional pull of ‘Nothing More’, which is a love song that stands on its own without the need for music labels.

Jarrod Dickenson’s ‘Ready The Horses’ will have immediate appeal to both country and Americana fans, but it’s the quality of the songs that will surely bring him much wider appeal.

He book ends the album with ‘I Won’t Quit’. And when he sings: “There’s still a long tall hill to climb, but I’ll get there in the end”, he leaves us in no doubt that he probably will. ****

4) “Pure Comedy” – Father John Misty

The centerpiece of this superlative album is the 13-minute track “Leaving LA” which throws shade on everything from the phony sweat shop jeans billboards on Sunset Strip to Fleetwood Mac. Sometimes sounding like 1970-era Elton John on steroids, Josh Tillman embodies the boozy, drugged out disenchantment of LA phoniness while sadly surrendering to the reality that he can check out any time he likes….but….

3) “Canyons of My Mind” – Andrew Combs

The three albums released by Nashville singer-songwriter Andrew Combs so far read like his personal journal. The youngest chapter, Worried Man, is stripped down and vulnerable, leaden with introspection and poetic pleading. All These Dreams was a slow shift outside his own heartache, introducing variations in tone and pop sensibility.

His latest, Canyons Of My Mind, continues this maturation with the introduction of existential ruminations, more ominous orchestral moments and the slightest taming of his twang in exchange for a higher register. Regardless of the narratives or the instrumental backdrop, Combs evolves subtly, with a grace that demonstrates his personal awareness and a musical sphere that offers variation without sacrificing his base.

Tracks like “Heart of Wonder”, “Blood Hunters” and “Better Way” introduce a grittier take on his countrypolitan sound, where Combs’ voice carries some added gravel alongside a grungier guitar line. The result is effective and well paired to the moodiness of the melodies. In other standout moments, his voice reaches a higher plane on “Dirty Rain” and “Hazel” where his crooning falsetto entrances like a melancholy lullaby.

While “Dirty Rain” is a verbally direct protest to gentrification and environmental neglect, “Bourgeois King” has little dialogue, speaking through panging keys and the gnashing of guitars, Combs sets the growling tone of political commentary. “Build a wall to block the enemy/build a wall to keep us free,” he repeats as an echoing chorus builds against mounting strings, ending on a climactic, instrumental breakdown.

The lyrics nod to phrases used in the most recent electioneering process without directly inserting judgement. They invite affecting contemplation over opinion. A welcome bookend, “What It Means To You,” the 11th and final track (a consistent number among his records), is a curveball, a beautiful duet with longtime collaborator, Caitlin Rose, that beckons the romantic grief and tender temperament of Worried Man .

We often equate the greatest singers with the widest range, the ones that tremble and roar. Andrew Combs has never been loud. He doesn’t dress loud, he doesn’t seek controversy or even talk abrasively. And he’s never had to wail to crescendo an emotion. He does something very pure and hard to find: choosing harmony and orchestral elegance over excess. He sings in the vein of Harry Nilsson, Kris Kristofferson and James Taylor, artists whose work carries an element of effortless sincerity. Combs has shared that timeless quality since his first record and Canyons Of My Mind is an assured and accomplished continuation of that.

2) “Elijah  Ocean” – Elijah Ocean

Ocean” – Elijah Ocean

Although I have been checking all of the other end of the year lists for this sun dappled tribute to Southern California, Elijah Ocean is truly an artist to watch. His embodiment of the spirit of co-operative hippie music and the Laurel Canyon sound is unmistakably present in every corner of his music. If we could have two number one albums of the year, this would be the other one.

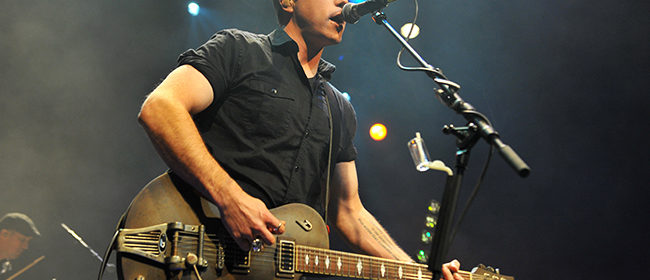

1) “The Nashville Sound” – Jason Isbell and The 400 Unit

Deserved recipient of multiple Grammy nominations, Jason Isbell has been putting out a body of work in the last half decade that far transcends his superlative work with the Drive By Truckers. Embodying all the accessibility of Don Henley without any of the baggage, this album delivers from start to finish. Worth its weight in Grammy gold.

Honorable Mentions:

“Thin” – Lowland Hum

“ Semper Femina” – Laura Marling

“A Long Way From Home” – Turnpike Troubadours

“Soul Of A Woman” – Sharon Jones & The DapKings