Jackson Browne Tribute To Ned Doheny

From Rolling Stone Magazine

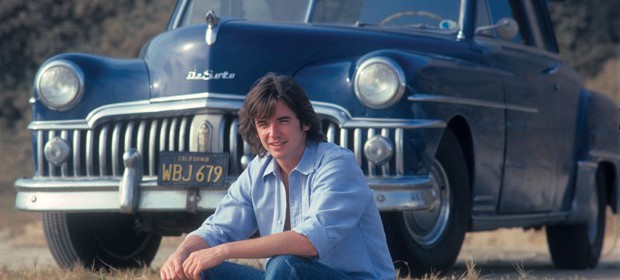

In Laurel Canyon musical lore, Seventies singer-songwriter Ned Doheny’s name registers as a blip compared to Joni Mitchell, David Crosby and the Eagles. Chicago reissue label Numero Group — whose stellar past compilations have resurrected artists and regional scenes — hopes to change that with the recently released compilation Separate Oceans. The career retrospective culls Doheny’s album cuts — 19 tracks of lilting folk, pop and soul — with previously unreleased demos and a lengthy essay on the offbeat songwriter.

Friend and fellow musican Jackson Browne was with Doheny through much of his prime years and tells Rolling Stone about the singer’s overlooked talents.

I met Ned Doheny in Laurel Canyon in 1968 and we became fast friends during a time when neither of us had any money, car or apartment. We each owned a guitar, and while I played folk styles, like finger picking and flatpicking and the most basic accompaniment needed for writing songs, Ned could really play. He played the acoustic guitar like it was an electric guitar. I think he might have played electric before acoustic, because his fluidity and confidence and inventiveness were those of someone hearing a lot of other instruments in his head. Not only did he play great guitar, his conversation was fluid and imaginative too and filled with strikingly visual language.

We both began staying at the house of a producer named Frazier Mohawk, who had introduced us. He lived about five houses up the hill from my manager’s house, where I had been crashing on the couch when I was in Los Angeles. This same producer introduced us to Warren Zevon and a whole lot of other songwriters and players. We became two of the players in a recording project on Elektra Records, which went by a number of names and went through several incarnations, and eventually broke up, with everyone going their own ways.

Ned and I played clubs for a while as a duo, and though I really liked his playing on my songs, I don’t think I added much to his. We spent a lot of time heading out to the high desert. While we were recording, we had been supported by the record company in a sort of communal way, and returning to L.A. we each got an apartment, him back in Laurel Canyon and me in Echo Park. My place cost $70 a month.

The pivotal event in our musical relationship was his borrowing my four-record set of The Greatest 64 Motown Hits. He would tell you it was his and that he didn’t get it from me, but he just didn’t want to give it back. Anyway, he wore it out. He didn’t just listen to it. He fused it with his molecular structure.

With that, he was off on a trajectory that has taken him from a desert-trekking, guitar-playing, surfing, singer-songwriter, to a producer/arranger whose grasp of rhythm and harmony is on a footing with the great record makers of the last 30 years. His singing too has developed steadily, and in a wonderful way. He sings higher and stronger than just about anybody. But his is not a narrative style of songwriting. His songs, though they could only have been written by him, could be sung by any great singer, and perhaps be sung best by a soul singer.

That widespread recognition has eluded him has more to do with his luck, or the lack of it, and the fact that he has pursued a course and embraced a musical terrain that is in stark contrast with his seeming identity. While he may be the embodiment of the phrase “play that funky music white boy,” both his erudition and his reclusive independence has set him apart from his peer group – and the audience – who would need to claim him as their own were he to become a pop star.

That he has an audience is certain, and I have met a number of young players who know his music and ponder his singular gifts.