If I had a time machine, I’d head for Laurel Canyon in the late 1960s.

At the time, Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon was a world unto itself — a desert collective, bursting with counter-culture creativity, a haven for the young and the restless, for folk singers, songwriters, artists and hippies, both sitting-in and rocking out.

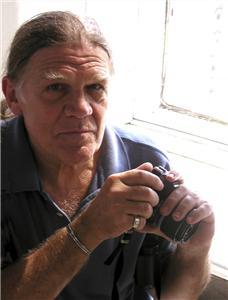

Henry Diltz captured all of it.

In 1966, Diltz was another young folk musician, a member of the Modern Folk Quartet, living in the Canyon.

So maybe fate played a part when he bought a $20 second-hand Japanese camera; after all, he was already nearing the hippies’ feared age of 30, and Diltz had never owned a camera in his life.

He began taking photos of his Canyon companions — Neil Young, Stephen Stills, David Crosby, Graham Nash, Joni Mitchell, Frank Zappa and Mama Cass, among them.

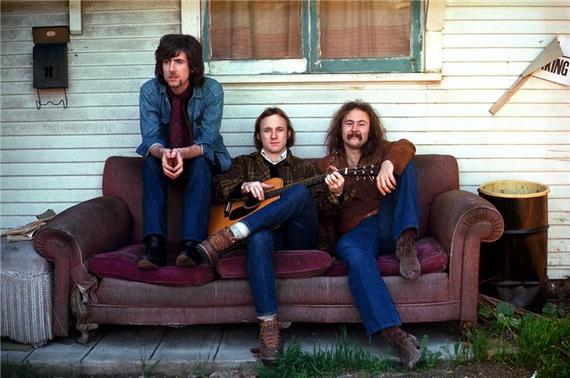

Some were used for his friends’ album covers. One of my favorites— and Diltz’s too — is the now-iconic cover for Crosby, Stills & Nash self-titled 1969 debut album, of the three, sitting in backwards order, on a discarded couch.

Others are just now black-and-white pieces of rock history. Ephemera, gems, artifacts documenting a critical time in American rock history.

Each of his slides in his archive now is like a tag on the bones of a bygone and fruitful era:

Slide: A wide-eyed wide-grinning Neil Young, playfully sharing his beer with a mounted moose head.

Slide: A come-hither-yet-somehow-girlishly-shy look from a young Linda Ronstadt.

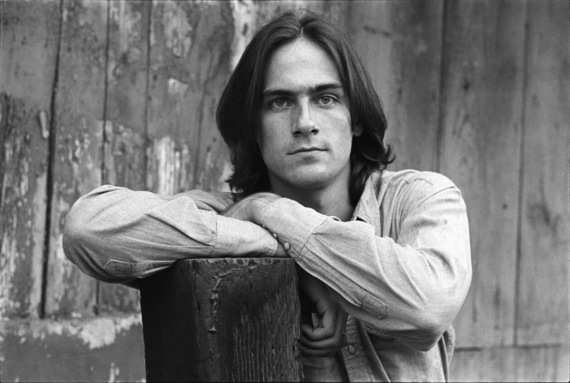

Slide: James Taylor, shaggy haired, picking on is guitar on a living room floor. Bob Seger sitting on a car hood. Jack Nicolson hanging back stage with The Monkees. Mick Jagger, Buffalo Springfield, Jimi Hendrix, Mama Cass, the Doors.

He was the official photographer for The Monkees. He was the official photographer at Woodstock.

Diltz is more than a rock photographer. He is a rock historian. HIs archives number in the hundreds of thousands.

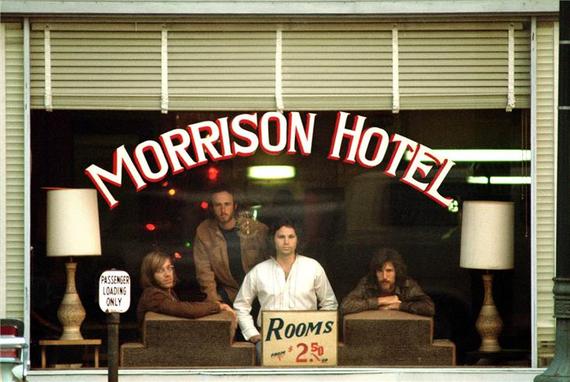

Today, Diltz is the co-founder of the Morrison Hotel Gallery along with Peter Blachley and Rich Horowitz in SoHo, New York City and in West Hollywood. The galleries specialize in fine-art music photography, including Diltz’s own works, along with some 120 other talented photographers. Both galleries will exhibit “Dont Look Back: Celebrating 50 years since Bob Dylan’s 1965 legendary acoustic concert tour in England and the Groundbreaking Documentary Film by DA Pennebaker.” This is the first gallery exhibit of Pennebaker’s work, featuring original movie posters and limited edition hand-signed stills.

Diltz calls Dylan “the poet of our generation.”

Here’s my conversation with the man who captured Laurel Canyon’s most fruitful era on film.

Daley: So how did you get into photography?

Diltz: In 1966, I had no want to be a photographer. My bandmates and I (from The Modern Folk Quartet) had bought these funky cameras and started photographing each other. It was a slide film, so we said, ‘Let’s get a projector,’ and when I saw that first slide, glowing eight-feet wide on the wall, it was an epiphany for me. I had no idea you could jump back into a moment so well and bring your friends with you.

A lot of my friends were well-known musicians who starting using my photos for record covers and magazines. I slid sideways into a photo career. (Eventually) I had this whole history of the California music scene on film.

Laurel Canyon was in the country — coyotes, raccoons, no sidewalks, no lawns. It was perfect for single people. We were all musicians up there, and in the beginning, we were all struggling folk singers, and then everyone started writing their own songs, and becoming successful. And I was right in the middle of it, luckily.

… The Modern Folk Quartet did a single we thought would make our career, but (we eventually disbanded in ‘66.) And there I was with a camera in my hands. With this new love, this obsession, this way of life. Every day I’d wake up and rush outside to find a new pictures to take. And all my hippie friends in Laurel Canyon slept till noon, and I usually did too, but now here I was up at 8 a.m. There was no one out but cats. I’d get down on my stomach and photograph the cats. (laughs.)

Daley: (laughs) Nice.

Diltz: It was an extension of being a musician, it was a way of entertaining my friends, but I didn’t have to play an instrument or sing. I’d say it was a complete accident, but maybe a guardian angle put a camera in my hands (laughs.) I don’t know… Being a musician first has helped me a great deal, because I really love all the musicians that I photograph.

Daley: So what was your big break?

Diltz: Stephen Stills invited me to a soundcheck on Redondo Beach, at the Third Eye in early 1966. There was a mural on the back wall outside the club (that caught my eye.) When (Buffalo Springfield) walked out, I thought, “Oh, some humans that could stand there and show dimensions of that mural.”

Daley: Right.

Diltz: So a magazine had interviewed Buffalo Springfield, and I got a call: “We hear you have a photo of Buffalo Springfield; we can pay you $100.” And that was my epiphany. I thought, “My God, I can make a living at this!” (laughs.)

…Then I got a call from (a magazine) who wanted to me photograph The Monkees in 1967. Then I became The Monkees’ (official) photographer for a year and half.

Daley: Wow. So jobs starting coming in after that?

Diltz: Jobs started coming from teen magazines. In between, I was photographing my friends — David Crosby, Mama Cass. They weren’t jobs; I was just photographing the people around me. I was always photographing all my friends. So that’s how I ended up with a huge archive.

Daley: How did you start doing album covers?

Diltz: I met a guy at a love-in at the Griffith Park, Gary Burden. Hippies would get together spontaneously on a Sunday afternoon, play music, schmooze. And I’d go and photograph the colorful people with tie-dye and colorful beads.

So Burden was a graphic designer and … Mama Cass said to him, “Why don’t you design my first album cover?” And then he met me; it was just good timing. And I went and photographed Mama Cass, and (Burden and I) just clicked. Between us, we knew everybody.

Daley: And I have to ask about the classic cover of Crosby Stills and Nash on the couch.

Diltz: (Burden and I) knew those guys; they were all friends of ours from years before they got together. They needed publicity pictures, so we drove around and found that house — it was perfect.

It was this little funky wooden house in West Hollywood, and they kind of spontaneously jumped on the couch. We didn’t plan on it being an album cover; they just needed publicity photos. We were spending the afternoon, just stopping here and there. After that house, we went to an antique clothing store. It was all real simple stuff, hanging out. Whatever happened, I’d photograph it. Then Gary would look through and pick the best that he thought would make the best album cover.

So a few days later, they named their band. And the photos was backwards. (They were sitting Nash, Stills, Crosby from left to right on the couch.) And I said, “Let’s go back and take photo in right order!” And we got in the car and went back to the spot and the house was gone — it had been torn down.

Daley: Oh my God!

Diltz: I know! (laughs.) Luckily, most of my pictures have a backstory, because they were adventures. If is was a studio photographer, there would be no story — it would be they came at 2 p.m. to the studio.

Daley: What do you mean adventures?

Diltz: We’d plan adventures. Like I went into the desert with The Eagles. It was their first album cover (self-titled, 1972.) We decided to drive out to Joshua Tree, to this big dessert, and spent the night, and spend the whole next day photographing. Gary would say, “Shoot everything that happens; film is the cheapest part.” But that was my nature anyway; I was a photographing machine. And then we had a slide show, and picked out the ones they liked.

We did the same thing with “Desperado” (1973.) We rented cowboy clothes, and got real guns with blank ammo, and went out to an old ghost town that had been a movie set in the 1930s, and they played cowboys for a day.

Daley: (laughs) That’s awesome. Do you have any favorites album covers?

Diltz: CSN, The Eagles that I mentioned. Jimmy Webb in his glider, Jackson Browne’s first cover. We did a number of America covers, at least six. Mama Cass covers, Steppenwolf, The Turtles.

Daley: You were also the official photographer at Woodstock. What was that like?

Diltz: I was like a pig in sh—. (laughs.)

Daley: (laughs.) I bet.

Diltz: I was like the young boy sneaking under the circus tent, seeing the show for free. It was a very busy time. I was there two weeks, photographing the building of the stage, then when the 400,000 people showed up, it was constant.

Interview has been edited and condensed.

Learn more about Diltz and his galleries, or purchase prints: here.

Lauren Daley is a freelance writer and music columnist. She tweets @laurendaley1.

That picture of Neil Young is nowhere near Laurel Canyon. Take it from a Californian.

That picture was taken at his ranch near La Honda, in San Mateo County, hundreds of miles north of Laurel Canyon. Take it from me, there is no wide swath of real estate like that in the Hollywood Hills.

Great picture, though…

And of course, Henry Diltz had a 40 year friendship, & as photographer for David Cassidy, from the teen mags, to chronicling his life in photos for all the world to remember, with his iconic albums of the 1970’s for Bell & RCA — great cultural times, RIP David Bruce Cassidy♡

Whooee – I had to laugh when I saw at the end of the article the interview was edited – but certainly not proofread!

“Diltz called Dylan the poet”…was just dropped in – did not flow into paragraph content.

Should be “angel”, not “angle”.

“If is was”…. What. The. Hey. ??

“Drive out to Joshua Tree, to this big dessert”…. Really? Spelled correctly throughout until this blatant oversight.

And yes, previous commentator correct, that photo was taken at Neil’s ranch in La Honda, not Laurel Canyon.

Proofreading and editing are a critical adjunct to the writers work but fast becoming obsolete in our hastily created Twitter-verse. I have to defer to the times but blatant oversights can get under the skin. Just had to do it!

My sincerest apologies. We will correct!